|

Richard F. Long, whose search for his roots led me to the land I describe in this story, died on December 5, 2011 at the age of 85. Uncle Dick inspired many in the family to pursue the story of the Long family's journey from Tipperary to Onondaga County. - Stephen Long This is picture of the 1994 Long Family Reunion on the site of their ancestor Thomas Longs farm in the southwestern corner of the town of Fabius, Onondaga County, NY. Richard F. Long is 4th from the right, in the back row, next to the woman in the white hat. Photo by Norah Breen |

|

| The Long View (PDF) |

The Long View by Stephen Long |

Thomas Long (1854-1908) and Bridget Ryan Long (1856-1905) and their family. Thomas was the son of the original pioneer Thomas Long (1811-1892). The younger Thomas was a tinsmith, first in the village of Pompey and then in Syracuse, NY. Richard F. Long and Stephen Long are descended from this Thomas. |

One sunny day in late spring, I was prowling around the land in central New York where my ancestors had farmed. A few years earlier, my brother and my uncle had found the barn's foundation, or what was left of it. I was hoping to find the cellar hole for the house. The walls of the barn's foundation, rising up six feet or so from ground level, were built from stone, using the readily available flat shale that was visible anywhere the water ran downhill with enough force to scour it out. Because they were mortared, I wondered whether this was a later barn than the one our forebears built in the 1860s. The windows and doors had vanished but their openings remained, and an apple tree with nascent green apples grew inside the barn walls. The crumbling barn, surrounded by sumac and thick tangles of honeysuckle and buckthorn, had become a party place. In one corner, there was a tarp spread out over some sticks to serve as a tent, and someone had made a hand-printed sign that read "The Alamo." Budweiser cans and faded bags of Slim Jims and Doritos lay sodden in another corner; in the center was a fire pit. I ventured out east of the barn into the spruce plantation, one of many that crews of CCCers had planted all through this area back in the 1930s when reforestation was the cure for abandoned farmland. This one was an overgrown mess with stunted trees and a web of roots above the ground making nice leg-hold traps for anyone not literally watching his step. Oddly, there were sporadic hardwoods that had seeded in and made their way to the sunlight, the occasional bole of a white ash gleaming in the company of the rough spruce. One of them had been chopped down at waist height, probably by one of the party boys who had an idea that it would be better firewood than the pitchy spruce. Farther in, I saw a larger interruption in the regular pattern of the planting, a bright patch of light through the trees. This hole in the spruce canopy was marked by lush green vegetation more honeysuckle and buckthorn, and tangled with grapevines. Within this island of vegetation was a hole, and by holding onto the vines, I was able to lower myself down into it. I'd found what I was looking for: a foundation, laid up in stone. The building it had supported was tiny compared to the barn about 16 by 24 feet but its four walls were in reasonably good condition, considering its age. If my detective work proved true, my great-great-grandfather and his family had dug this cellar hole by hand in 1862 when they followed their dream and bought 250 acres a few miles from the village of Tully where they'd settled 10 years before. They'd come to the rolling hills of Onondaga County following family and neighbors from the rolling hills of Tipperary, all of whom were escaping the potato famine that had decimated an already malnourished peasantry. In my wanderings around our home in Vermont, I've found a number of cellar holes, and it's always a treat to come upon these signs of farm life that have been all but erased by the now mature forest. But this was more than a treat: it was all that remained of my ancestors' dreams of going back to the farm life they'd known in the old country. The dream lasted only 25 years. Along the way, they built the house and barn, raised livestock and grain, and struggled with debt almost their entire tenure. I've seen the chattel mortgages they entered into, each year putting up their 24 dairy cows and their 10-year-old horse or a certain number of tons of hay as collateral for a loan of $1,000 or thereabouts. It was never through a bank, but a personal loan from a man named Colby, the same man who had sold them the land. Evidently, they were able to repay the loan, because each year Colby made another loan to them. Today, the land is adjacent to the 4200-acre Heiberg Memorial Forest, one of the satellite campuses of SUNY-Environmental Science and Forestry. Established in 1950, Heiberg is now home to classrooms, research and monitoring stations, an active sugarbush and sugar house, and a network of nature trails that are enjoyed by birders, hikers, and berrypickers. Our land I say ours despite the fact that my family owned it for such a short time is now owned by the ESF College Foundation, and it contains some of the college's study plots. A history of Heiberg Forest put together by Bill Ehlers, who was once the forest supervisor and has since retired, gives an indication of what the 19th century farmers were up against: "At these higher elevations (1360 to 2020 feet) there is a relatively short growing season or frost-free period. The soils are derived from local bedrock of mostly interbedded shale and some sandstone left by the glaciers as a thin mantel of till. The soils are strongly acid, poorly drained, and comparatively infertile." Just like the Finger Lakes, which start just west of here, the ridges and lakes all run north-south, and the hilltops were all scrubbed relatively flat by the Wisconsin glacier: they're flat enough to farm, but most of the topsoil has unfortunately been deposited in the lush valley below. I left the spruce plantation and crossed the powerline right of way an interesting bisection of one 20th century human construct by another into a Scot's pine plantation, before I found the stream I was looking for. As I approached it, the plantation gave way to a forest of hemlocks and red maples. In deep shade, the stream stepped its way down lazily over a series of flat shelves of bedrock, forming pools so angular that they look landscaped rather than natural. The stream's last run led to the edge of a dramatic carving out of the hillside and a spectacular cascade. It's beautiful, indeed, though I couldn't help but think that their position at the top of this waterfall was directly related to their farming prospects. From it, they could see the lush farmland in the valley below (land that, by the way, is still farmed today), but that's as close as they got to productive land. We know where they lived in Tully in the years leading up to their move to the farm, and we know where they lived after they left. One of the sons, my great-grandfather, ventured off to Syracuse after less than 10 years on the farm. A burly man with a walrus mustache, he became a tinsmith and started a sheet metal business in downtown Syracuse. His first residences as he was getting settled were in a section of downtown that lasted only until I-81 was built in the 1960s. But even if those houses were still standing, I know that what interests me about the family's early history in this country is this homestead they built for themselves out in the country. Am I simply being drawn to a romantic notion of the immigrant family making a new life for themselves by tilling the soil? Surely, there's some of that we are, after all, a family of Irish, no strangers to embroidered history. But there's nothing particularly romantic about their fate. In the immediate family that made the trip, the only one who lived past his 50s was the patriarch, who lasted 80 or so years. His wife died at 53, and two of her children pre-deceased her. Still, I do find nobility in their struggling on in the face of annual payments that could only be made if the crop was sufficient and the market good. When the future tinsmith left the farm, he left behind his father and older brother who kept farming until 1887, at which point they too moved to the city. Since then, every person in every generation of my family has lived an urban life but with one eye on the country. The term "Sunday driver" could have been coined for my grandfather, who sold Chevrolets and taught the new owners how to drive them. On Sunday, he'd drive his family out to Tully, Truxton, and Fabius to see the beautiful countryside. My father did the same with his five kids, though he took us north instead of south. My wife and I have been living a rural life for 20 years now. It would be nice to say that we've been able to make a living from the land, but try as we might, we couldn't turn a profit raising a flock of sheep. Our occasional timber sales provide firewood and help pay the costs of owning this land. We grow vegetables and fruit and have meat in the freezer that's either raised or hunted, but I am by no means a successful subsistence farmer. Our jobs have allowed us to live in the country but not depend completely on the land to support us. I imagine my great-great-grandfather in 1887, as an old man of 75 or so, looking down with envy from his perch at the top of the waterfall at the fertile valley below. After 25 years of toil, he couldn't make his hill farm pay. Its beauty and the hard work it required were inextricably linked, and he knew that he couldn't keep it going, that he and his farmer son with his own growing family would need to move to town. He must have felt that he had failed. What he might not have realized is that he was just part of the shaking out of the agricultural economy. There was no margin for error, and the countryside was being emptied of farmers, some who moved west and some who moved to town. That mass emigration set the stage for the reforestation either by planting or by forest succession of our region. Today, rural lands are increasingly home to people like us, people who love the land but aren't dependent on it for a living. I'm heartened when others are able to coax a living from the woods or the farm, and I admire them for beating the odds. To be successful requires hard work, flexibility, an ability to innovate, a great sense of markets, and a healthy dose of good fortune. Those still working the land today will leave behind more than fragments of their lives to be pieced together by their descendants on Sunday drives they may even bequeath the land itself.

|

A reunion photo of Dick Long (on the left) and Fran Breen was taken in 1994 at the site of the Thomas Long barn. Fran is married to one of the descendants of Lawrence Long (eldest son of Thomas Long the pioneer). Photo by Norah Breen. |

|

Another picture from the 1994 reunion showing the over grown cellar hole of the old homestead. |

|

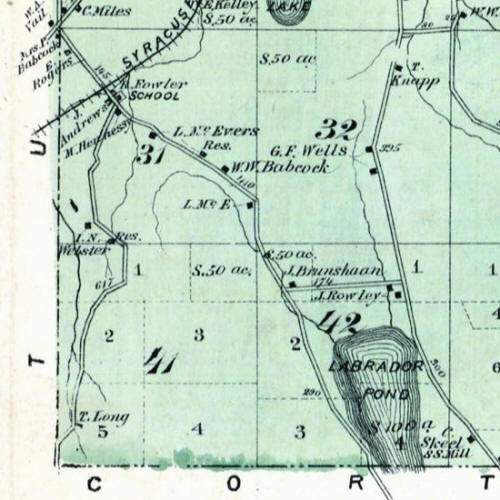

This 1874 map of the southwestern corner of the Town of Fabius shows the property of Thomas Long in Sub-division 5 of Lot # 41 |

|

Copyright © 2006 - Michael F. McGraw

|

Upperchurch Connections |

What's New? |

|||

|

|

||||

|

||||